Overcoming the gender leadership gap and women only development programmes

6 min read

We’ve always experienced some discomfort about the idea of providing a skill development programme designed for women-only groups, despite the demand from organisations and women themselves.

Recently our discomfort has been echoed by some of our clients who have concerns that women-only training actually undermines equality.

Similarly to the arguments made towards workplace quotas, some might argue that women-only training is discriminatory, patronising and counter- productively underlines differences rather than supporting equal opportunities.

Let’s start with a few thoughts about women-only training before we look at how it fits into the bigger picture and explore what work needs to be done towards gender balance at all levels of an organisation.

We believe that women-only groups do have their place, particularly in male dominated organisations, industries and cultures. In the right context, they are welcomed by women as they provide a comfortable environment for discussion and an opportunity to talk about particular perspectives that women experience in (and out of) the workplace.

Earlier this year we gave an International Women’s Day talk about unconscious bias to a group of women solicitors and barristers. They were all ambitious and successful in their respective roles, however in that female only environment there was an outpouring of stories, frustrations, anecdotes, ideas and empathy.

There were a couple of shocking stories but mostly they were the wearing, everyday examples of overt or unconscious stereotyping, such as the partner of a mid-sized firm who talked about a client continually requesting to speak to a (more junior) male colleague on the assumption he was the senior partner.

There was a strong sense amongst that group that they wouldn’t share these issues in a mixed group and having a place to talk about them and share suggestions and positive approaches was welcome and valuable.

Whether we recognise it or not, most organisations are designed to suit a male stereotype. We are so used to that stereotype being ‘how work is’ that we may not even be aware of it. Long, inflexible working hours, career progression paths that require regular international travel (assuming a ‘trailing spouse’), our idea of a strong leader correlating with stereotypical male traits; unconscious bias around behaviour that is appropriate or acceptable for a man or woman; the tendency towards gendered roles (women on boards are often HR directors) and more.

It’s often nothing noticeable, women will just feel that they don’t have quite as comfortable relationships with senior managers as the men do, they seem to be promoted less quickly, they are overlooked for challenging assignments. They may blame it on themselves, become frustrated with the organisation or change jobs in an attempt to find a better environment. (It’s worth noting that while this stereotypical male work environment can be challenging for women, it also doesn’t suit the many men who don’t fit that narrow stereotype).

We support the argument made by Avivah Wittenberg-Coxi that women are equal but different. In her HBR article ‘To hold women back keep treating them like men’ she explains that she’s not talking about innate differences (the jury is out on the extent to which these exist) but the well researched gender differences caused by the way that girls and boys are brought up, the expectations of them by family and society, societal norms, their experiences at school and in work.

These life experiences create some simple but noticeable differences between men and women in areas such as communication styles, career cycles and attitudes towards power and ambition.

This means it’s important not to confuse ‘equal’ with ‘the same’. So while we want equality for men and women at work, it’s not always useful to interpret that as treating women in the same way as men. That may sound counter-intuitive, like we’re singling women out for special treatment.

The issue is that because of the socialised differences between men and women, if women are treated the same as men in a male stereotyped environment with a male model of leadership then it is much harder for women to be successful than it is for men. Thus it being more helpful to think about women being ‘equal but different’.

So is any women-only training useful? We believe it is. The supportive, empathetic dynamic of a women- only group, plus the particular challenges that women face from male-stereotyped environments, means that there is a desire from many women (regardless of their seniority) to understand better how their own socialised expectations and the stereotyped expectations of others may have an influence on their behaviour and its interpretation at work.

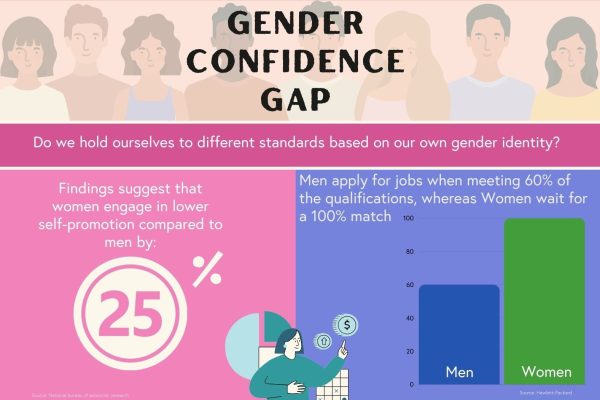

Study after study indicates that these things can negatively influence women’s confidence in their abilities, their perception of their own potential, and their ability to articulate and express their needs and ambitions.

From our experience, even very senior, successful women talk about having to overcome a reluctance to put themselves forward, or times when they feel they have ‘held themselves back’, or having to force themselves to do something – such as networking – that felt very uncomfortable (A McKinsey study found that more than 50% of women felt that they held themselves back from accelerated growthii).

The women who feel they have overcome their reluctance tend to express exasperation with other women who don’t speak up or who are self-deprecating, seeing them as contributing to the stereotype.

However, none of this behaviour is surprising given that many work environments are not designed to support – or sometimes even value – the communication and leadership preferences favoured by many women. This needs to change, but in the meantime it is helpful for women to have the skills to become more effective agents for change in the existing working environment.

It’s worth noting here that nothing we say about gender is true for any one individual, but there are norms that we see in women in general, men in general and in organisations.

So women-only programmes can provide participants with an awareness of bias and its implications, and opportunity to discuss strategies for dealing with current organisational cultures. They also help build skills in areas where many women have had enough of feeling uncomfortable and at a disadvantage, such as self- advocacy, negotiation on behalf of themselves, asking for things and taking credit.

This is not about ‘fixing women’; it’s about personal and professional development in areas which go against others’ (both men and women’s) expectations and stereotypes about ‘appropriate’ behaviour for women. We are all aware of the double bind that many women find themselves in when being a strong female leader is seen to be diametrically opposed to being liked.

This is not something that men have to deal with as all these skills and behaviours are expected in men (whether they actually have them or not).

However. And it’s a big however… gender balance in organisations will not be achieved by women-only programmes, or by developing professional skills in women. As we’ve described above, we think the content of women-only programmes is both valuable to and welcomed by women. The problem is when the presence of such a programme positions the lack of equality in an organisation as a ‘women’s problem’, or a ‘problem with women’.

Women-only networks, diversity groups or training programmes are not the solution to gender inequality at work. This can only be tackled by men and women jointly, by prioritising the issue at the top of organisations and making it current and relevant throughout.

Critically, it requires that the culture of the organisation is examined and changed where necessary so that it is equally attractive to women and men. The organisation that says: ‘it’s hard to find women who fit our company culture’ has got the diagnosis of the issue the wrong way round.

Changing the culture needs to start from the point of the economic argument and business goals and the aim should be towards gender balance at all levels in the organisations (and all functions) rather than promoting women’s leadership.

The culture change needs to be owned by leaders and managers, rather than by women as a separate group. Men need to be responsible for and driving change as much as women. They can’t be positioned as ‘champions’ of another group’s cause (again, this positions gender equality as a women’s group issue).

This type of culture change is not easy and requires the willingness to acknowledge existing bias, identify and prioritise the changes required, drive creativity and flexibility in solutions. How to create gender balance needs to become a conversation which everyone has, at all levels in the organisation – not something that comes as a presentation from a diversity officer.

Awareness of unconscious bias and the ability to attract, work with, develop and retain both men and women equally, is a critical leadership and management competency for successful individuals and progressive organisations.

References:

ii Joanna Barsh & Lareina Yee, “Unlocking the full potential of women at work”, McKinsey & Company 2012